Decades after independence, African politics remains shaped by its colonial past and post-colonial challenges. While independence brought initial optimism, many nations have faced persistent struggles with corruption, civil conflicts, and authoritarian governance.

In numerous countries across the continent, political opposition and citizens continue to face intimidation and repression, with activists risking arrest or physical harm in their pursuit of democratic values.

This landscape of political control and resistance is now experiencing a profound shift. As digital platforms become increasingly central to daily life, they’re transforming how power is exercised and challenged.

A new battleground

Once primarily a tool for personal connections, social media has evolved into channels for communication, opinion-shaping, and information exchange. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok have become critical to Africa’s political, social, and economic landscape, particularly due to the widespread adoption of mobile technology and affordable data plans in the 2000s and 2010s.

Across platforms, African activists have found unique ways to leverage these digital tools: organising real-time protests on Twitter, building community networks on Facebook, documenting human rights abuses through TikTok and YouTube, and maintaining secure communication channels via WhatsApp and Telegram.

When authorities block one platform, activists quickly adapt, shifting conversations across applications and using VPNs to bypass restrictions. This digital resilience mirrors the long history of resistance to oppression on the continent.

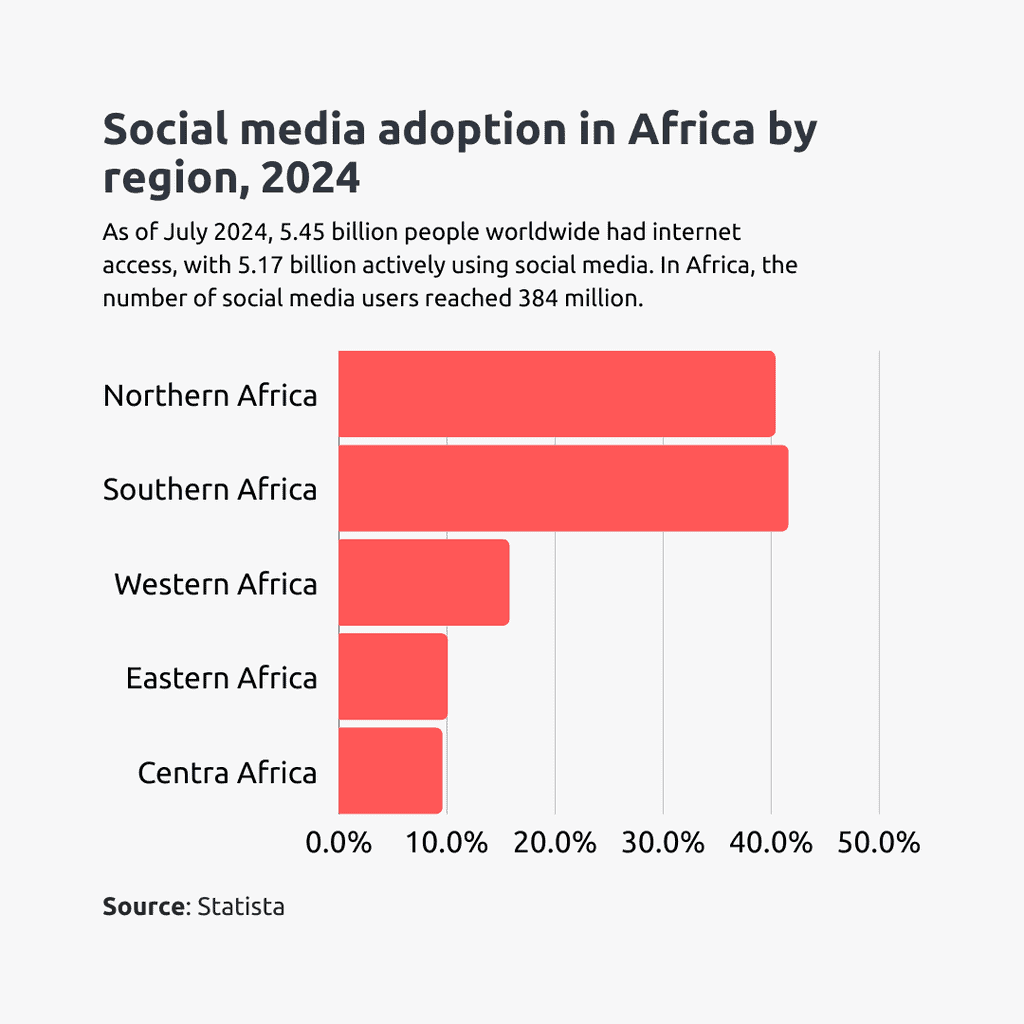

As of July 2024, 5.45 billion people, about 67% of the world’s population, had internet access, and 5.17 billion (63.7%) engaged on social media. Africa had 384 million social media users in 2023, with Northern and Southern Africa leading in connectivity while Central Africa trailed. Facebook dominates globally, with 3.065 billion active users, especially among the 25-34 demographic, whereas Instagram and TikTok primarily engage young adults.

When hashtags challenge authority

This reach has transformed local issues into international discussions. Take, for instance, Nigeria’s #EndSARS protests, which highlighted police brutality and human rights abuses, gained global attention after violent incidents against protesters. Namibia’s #ShutItAllDown movement brought attention to gender-based violence.

Guinea’s #PrayForGuinea hashtag raised awareness of election violence, and Congo’s #CongoIsBleeding campaign spotlighted humanitarian crises tied to cobalt mining. South Africa’s #AmINext responded to gender violence, and Ghana’s #FixTheCountry and #OccupyJulorbiHouse demanded government accountability on socio-economic issues and highlighted citizens’ frustration with corruption and mismanagement.

The use of these platforms shows how social media is challenging traditional power dynamics. Marginalised voices are no longer confined by geography, reaching across borders and echoing globally. It’s become a space to share live experiences, find solidarity with the rest of the world, and offer counter-narratives to regimes seeking to control public discourse.

This power shift is accelerated by social media’s capacity for instant information sharing. What starts as a single post can reach millions within minutes, with users sharing, commenting, and amplifying messages. This immediacy means that events unfold in real-time before a global audience, making it increasingly challenging to control narratives or suppress information.

Bots, propaganda, and digital harassment

Faced with a real-time loss of control, governments now seek to turn social media’s power against its users. Authoritarian regimes in Africa use these platforms to suppress dissent, spread propaganda, and manipulate public perception.

During protests, Internet shutdowns and social media blocks are employed to silence public discourse and disrupt organised resistance. In 2021, the Nigerian government banned Twitter following EndSARS protests, igniting discussions on alternative platforms. In Uganda and Tanzania, similar restrictions were imposed, with authorities blocking platforms to suppress dissent.

Beyond silencing voices through shutdowns and bans, governments are weaponising social media for surveillance. Security forces now monitor digital spaces to track and target individuals involved in protests, activism, or opposition politics. In Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, and Sudan, this digital surveillance has led to direct consequences—activists, journalists, and ordinary citizens face harassment for their social media posts.

Even more troubling is the rise of bots, automated accounts created to spread misinformation and disinformation. Governments deploy armies of bots—automated accounts—to flood platforms with pro-regime propaganda and drown out opposition voices. During elections and protests, these bots create an illusion of popular support for the government while attacking and intimidating critics.

The strategy is clear: if you can’t silence dissent directly, overwhelm it with manufactured noise.

It goes further, as paid groups of users use the tool to the same effect. Political opponents, journalists, and activists are often targeted with threats, doxxing, and online abuse, usually funded by the government in power. The harassment extends beyond social media, with people frequently facing physical threats because of their online activism.

Protecting digital rights

The transformation of social media from a space for connection into a battlefield for political power demands our immediate attention and action.

When Nigeria’s government banned Twitter following #EndSARS protests, when Ugandan authorities shut down platforms during elections, and when Ethiopian officials surveilled citizens’ online activities, they revealed an uncomfortable truth: the tools that gave voice to the marginalised have become weapons in the hands of the powerful.

But this is not just another story of oppression. From #ShutItAllDown in Namibia to #FixTheCountry in Ghana, digital platforms have enabled unprecedented mobilisation against injustice. These platforms have created cracks in the foundations of traditional power structures, allowing marginalised voices to echo globally.

We need decisive action to preserve and strengthen these digital spaces of resistance.

Governments must be pressured to establish clear digital rights frameworks that prevent internet shutdowns and surveillance. Social media companies must invest in understanding Africa’s complex political landscapes—bot networks and state-sponsored harassment campaigns look different in Accra than they do in London. Civil society organisations must promote digital security skills while telecommunications companies expand affordable access to underserved regions.

Most crucially, we must recognise that this is not merely about technology—it’s about power. As authoritarian forces adapt to using these platforms for control, our response must be equally sophisticated. The future of African democracy may well depend on who shapes these digital spaces: those who seek to silence or those who strive to be heard.

4 Comments. Leave new

Very concise and Informative

Was discussing this with a colleague at work. Social media is influencing the socio-economic aspect more than ever.

People are also more interested in politics now because they easily get information and data on the media.

Infact, radio stations and television media houses pick updates from social media

Social Media is definitely influencing political stance. You can’t just walk over anyone these days. Social media wil expose you.

Great piece